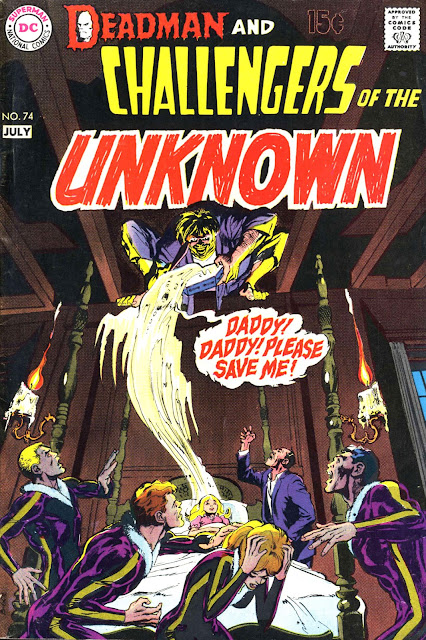

GREEN LANTERN #79 Sept 1970

"My Redskin brothers find you GUILTY! And I am your EXECUTIONER!" exclaims Green Arrow, taking aim at Green Lantern who is tied to a totem pole. The two heroes, supposedly friends are divided. Although they are surely both good guys, altruistic and compassionate they are on opposite sides. Division.

Despite being expertly rendered as always by artist Neal Adams, I can't help but be disappointed by a cover which not only acts as something of a spoiler for what follows in this issue, but which also depicts a scene that never actually takes place in the story itself. However, its purpose would have been to sell issues and on that count it works. Besides, it effectively encapsulates the conflict between the two characters. The division.

GREEN LANTERN #79 focuses its attention on the mistreatment of Native Americans (which in 1970 were still commonly called Red Indians or 'Injuns' or 'Redskins' as GA calls them). The story itself is written completely in service to the message, that the US government is guilty of exploitation and will resort to any means in pursuing its own greedy ends.

But, as I've already suggested, this issue also concerns itself primarily with division. Until now the story arc has featured a politically naive Green Lantern being schooled somewhat by the politically aware but headstrong Green Arrow. How you feel about these characters will depend principally I guess on your own political leanings. Certainly the responses I have received from readers of my previous blog entries on this title suggest this to be the case. In this issue the superheroes become more divided. Their differences of opinion lead to a deep division and its seems fitting that I am discovering and reading these issues at a time when division in both the UK and the USA seem to be so marked and so troubling.

At the start of the story writer Denny O'Neil introduces this issue's principal antagonists, Theodore Pudd and Pierre O'Rourke. The pair wave guns at a Native American they have hunted down like an animal and are about to murder him in cold blood.

The previous issue of GREEN LANTERN, #78, had dealt with white supremacy and Pudd is immediately revealed to have similar prejudices. He describes the Native Americans as "filthy savages", "animals" and "creatures" which he wants removed from his "community".

Interestingly he also condemns the white supremacists in #78, not because of their beliefs, but rather because they were "filthy hippies" prompting Green Arrow's disgust.

As he has done in the issues immediately prior to this, O'Neil presents an opposition between the wealthy and powerful and those who are poor and disenfranchised. The Native American blames the Government directly of corruption against his people.

But his angry claim that GA is "lording it over" him with his "moral superiority routine" exposes the weakness of his defence.

Having parted ways, Green Lantern however resolves to investigate the matter further, admitting "maybe I was wrong", a sign that he is undergoing change, as suggested he would at the onset of this story arc in #76.

Within a few pages Green Lantern muses on this change-- "I once thought that this ring, plus my oath, plus good intentions, plus will power-- equaled a certain force for JUSTICE!" But he recognises now that the world is not easily divided into right and wrong, good and bad--

A brief interlude in which GL questions the Guardian as to why humans are "so confused and contrary" elicits a response which attempts to address this uncertainty-- The Guardian cannot outright condemn the instances of violence he has observed, since they come from the same place in humanity as the "spirit" which leads to great technological advances. The writer seems to be suggesting that violence when meted out by the strong against the weak or vulnerable cannot of course be condoned, but that violence perpetrated by "heroes" against the oppressors and exploiters is another matter entirely. A fitting summation when defending the actions of superheroes who readily overpower their adversaries with volleys of superpowered punches and kicks.

Then when he is presented with the inevitable knowledge that O'Rourke does not have a legitimate claim to the land he has taken control of, Green Lantern is forced to grapple with his system of beliefs again. A single wordless panel suggests GL's anger and frustration before four dynamic frames follow in which he is depicted soaring in four different directions to emphasise the confusion his challenged beliefs are causing him.

The story then shifts to catch up with Green Arrow and Black Canary, whose recent brainwashing had turned her into the murderous tool of a charismatic cult leader. Green Arrow's empathetic nature is underlined in this panel showing him crouching down to speak to her, coming down to her level like an understanding parent or teacher to a troubled child. It's a great visual moment, the fact of Canary turning away shamefacedly from her friend, with her head bowed, reinforces, not only her shame, but also her vulnerability.

Black Canary's own compassionate nature has led her to a Native American town where she is attempting to bring help and support to others she recognises as being vulnerable themselves.

Two issues previously Green Arrow had encountered a downtrodden community, when he had helped overthrow a dictatorial mine-owner who had broken the spirit of the inhabitants of the town of Desolation. This time he goes to the extraordinary measure of disguising himself as "the spirit of Ulysses Star", the legendary chief of the tribe from a century earlier.

I feel this is the weak point in the story overall. As well as the somewhat ridiculous idea that GA could convincingly disguise himself as this figure, albeit with the noblest intentions, there is the nagging problem that his intervention smacks of what is now termed the White Saviour Narrative. Sociologist Matthew Hughey summarises this narrative idea, common to a considerable number of films and other texts, as centring on "a white person - the savior" who encounters "a non-white group ... who experiences conflict and struggle with others" and then "as a teacher, mentor, lawyer, military hero ... or wannabe Native American warrior, is able to physically save ... the community of folks of color". He could have been writing specifically about this story!

When Green Lantern shows up with Congressman Sullivan he immediately comes up against Green Arrow who has no faith in the US Government to effectively address the plight of the Native Americans. O'Neil hasn't shown the pair of superheroes to be so much in conflict with each other in previous issues. But here the difference between GA's instinct for direct and immediate action and GL's natural recourse to following legal processes bubbles over completely.

Of course, Green Arrow's Ulysses Star costume is entirely yellow, rendering Green Lantern's ring powerless. The third frame in the following triptych is incredibly effective as the superheroes respectively drop the means of their superpowers and confront each other instead as two men--

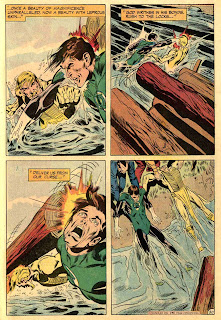

The fight sequence which follows is little short of remarkable. In the cooling, cleansing waters of the river the two men slug it out wordlessly as they are watched from the shore by the story's other characters. The captions again afford O'Neil the opportunity to stray into the poetic, and offer an insight into what lies behind their conflict-- We read of "the elemental struggle", that each man is "fired by a belief in justice". Then we see them rip each others' masks off desperately-- this action might be intended to expose and weaken, but it can equally be interpreted as an unconscious attempt to see beneath the surface, to understand each others' thinking. Indeed, the caption tells us that in that moment "they look, they see, and they know they are looking upon their nation, their world, in the agonized expression of a friend's face". It's a moment which could bring them together were their emotions not so highly charged. But it doesn't and they continue to fight even more aggressively. Division.

As I write this on November 20, 2020 it is hard not to think of division, of the conflict currently raging across America. On November 3rd the nation went to the polls, the results of which were immediately disputed by the incumbent President, Donald Trump. For days the overall result hung in the balance, as one by one a handful of swing states declared their totals. Eventually the winner was clear -- Joe Biden secured more votes and was recognised across America and around the world as President-elect. But, as we know, Trump's claims that the election was rigged kept coming, and continue to come. He refuses to concede that he has lost and his supporters refuse to concede it too.

And so, the United States of America, so radically divided over the past four years, remains divided -- and just like the brawling characters in GREEN LANTERN #79, supporters of Biden and supporters of Trump seem locked in an "elemental struggle", and each side is seemingly "fired by a belief in justice" so different to each other's.

And so we wait, the whole world waits, until "the masks fall", until the opposing sides "look" and "see" and "know they are looking upon their nation, their world, in the agonized expression of a friend's face". And we hope that the next stage is not what happens next in this storyline. Because here the two characters just keep slugging it out relentlessly until they are knocked unconscious by a falling log and have to be rescued themselves by others to stop them from drowning in the harsh, unforgiving waters of the river.

O'Neil also takes the opportunity to include lines from Norman Mailer's THE ARMIES OF THE NIGHT-- "Brood on that country who expresses our will... She is America... Once a beauty of magnificence unparalleled, now a beauty with leprous skin... God writhes in his bonds. Rush to the locks... Deliver us from the curse..." Again I am forced to wonder at what the reaction of this across the title's wider readership might have been. Mailer's book describes his account of an anti-Vietnam War rally in 1967, and it is more than likely that the majority of GREEN LANTERN juvenile readers would have been unaware of this text's existence, although maybe their parents were.

The lines quoted do not hint at the autobiographical novel's controversial subject matter, but their inclusion here confirm O'Neil's subversive intent. The chosen lines resonate with the writer's notion of a mythical America, untainted and essentially 'good' which the superheroes are in search of. And while O'Neil's purpose is yearning for such "splendor", as the Guardian terms it, is in itself honourable, I would concede reluctantly that it is also fundamentally naive and flawed. We do not have to look too closely at how current notions to 'Make America Great Again' are really just a subterfuge to encourage intolerance and inequality or to understand how nostalgia and mythologising a nation's past can be used for more pernicious ends. To create division.

The same is true of what is happening here in the UK with Brexit. The promise to "Take Back Control" spoke to those with a nostalgic, mythologised concept of Britain's past and is fuelled by a misunderstanding and intolerance of immigration and by a suspicion of unity with others from differing backgrounds and cultures.

The past four years have been characterised by a division of the British populace into 'remainers' and 'leavers' as insidious as division on racial or religious terms. And as I commented on in my article on GREEN LANTERN #77, division is one of the most potent weapons in the arsenal of the demagogue.

So, yes, the lines quoted from Norman Mailer's book might well have proved baffling for readers expecting more traditional storytelling. But we should also note that amongst its original readership, this title also had its share of older readers prepared to engage with O'Neil's challenging narrative approach. The letters page of #79 focuses on this story arc's first issue, GREEN LANTERN #76, and it seems that reactions among fans is as also a case of division, albeit more articulate and reasonable than a couple of guys beating hell out of each other in a river. On the one side reader Juan Cole declares #76 to have "revolutionized my entire concept of what a superhero should and could be". He praises O'Neil and Adams for their portrayal of "true human beings", recognising the "realism" and "relevance" of "far and away DC's best magazine". In other words, he seems to embracing change in the genre and the creators' desire to provoke awareness of issues such as civil rights.

On the other side is reader Lee Breakiron who asserts in that "The purpose of comics is to entertain, not to propagandize". He asserts that the accusation in #76 that Green Lantern has "done little for 'black skins'" is counterbalanced by the fact that equally he has not ever done anything "specifically for 'white skins'". Breakiron's comments regarding "the Communists in Vietnam" suggest he would have little sympathy with the contents of Norman Mailer's quoted text in this issue. For this reader the comicbook genre does not need changing and politically conscious material ought not to be part of it.

You can find similar arguments today amongst fans of comics as well as other forms of popular culture. There are those who bemoan contemporary shifts in awareness and brandish terms like "woke", "libtard" and "SJW" as frustratedly as the flying fists in the river, claiming that their beloved comic or film franchise should be entertainment pure and simple with no other agenda. Then there are others who embrace story-telling's potential to overcome prejudice and educate as well as entertain. Like the Juan Cole of 1970 they are open-minded and excited by change. As a lifelong fan of DOCTOR WHO it is alarming to see so much hatred meted out recently against the current creative team, especially from those who claim that the show has never been overtly political until the advent of Jodie Whittaker's Doctor under the stewardship of Chris Chibnall. Like the Lee Breakiron of 1970 they argue that the purpose of a show like DOCTOR WHO is to entertain not to propagandize. I can't help thinking that what they actually mean is that they don't like so many non-white faces in the cast. And they don't like a female protagonist. And so many other things which upset their amoebic view of the world. DOCTOR WHO is not for these people and, let's be honest, it never was.

But I digress. It is evident to me coming to these issues of GREEN LANTERN 50 years after their original publication that, all faults aside, they offer a fascinating insight into a period of great pessimism, but conversely great optimism. And in this issue particularly that division is one of the world's greatest ills. In the story's campfire coda, the men recognise that their fighting "didn't settle anything" and that "the problem still exists".

The Guardian's optimistic appraisal is that there is a solution-- an end to violence. Of division. Fifty years on and we're still waiting for it.

My thoughts on other GREEN LANTERN issues can be found by clicking on the images below--

Follow @top_notch_tosh

Comments

Post a Comment