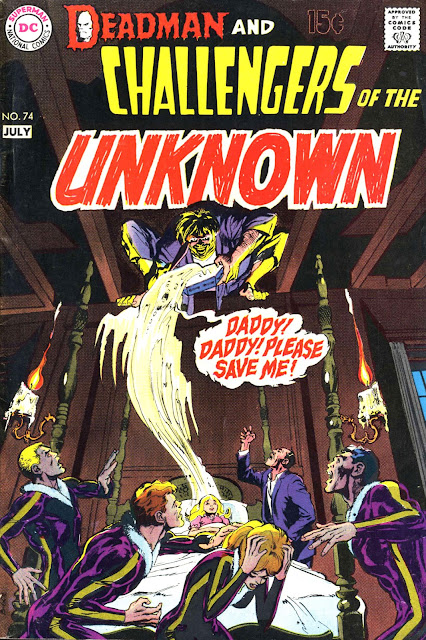

HOUSE OF MYSTERY #190 Jan 1971

"A Witch must die!" declares the caption on the front cover of HOUSE OF MYSTERY #190. It's another atmospheric Neal Adams image, albeit a less obviously effective offering than some of his previous images for DC's Horror anthologies. This time the usual three kids are huddled behind some gravestones, seemingly hiding from a broomstick-riding witch whose silhouette stands out against a luminous yellow moon.

In the foreground, however, a second witch appears to be approaching the kids, unseen by them apart from by the little girl, whose backward glance draws our eye to the advancing figure. It's a neat optical trick on the behalf of Adams. While he employs a fairly standard triangular structure in the positions of the three children and the framing triangle of the spooky house, all attention should be on the single lit window, or otherwise on the flying witch. The girl's glance though distracts away from what the boys are watching, forcing us to shift our own focus jarringly to the real menace. The fact that this figure is barely even in the frame is another masterful element-- a lesser artist might have allowed the second witch to dominate the frame more. Adams clearly understands that understatement is more effective when eliciting the viewers' fears, choosing to suggest far more than is depicted, to obscure more than is shown.

And it's all in the girl's eyes. The terror, the innocence... and the knowledge. Knowledge of exactly what is stalking these kids and what we ourselves are not able to see.

It is fitting then that, throughout this particular issue of HOUSE OF MYSTERY, the characters' eyes are depicted so interestingly and tell the stories much more effectively than any of the speech balloons or narrative panels.

And that's just as well, because to be fair the narratives themselves are somewhat disappointing, both stories hinging on twist endings which can be seen coming from incredibly early on.

Even Sergio Arragones' opening splash page, a portrait of the title's host, Cain, is all about the eyes. Both Cain's pet cat and gargoyle stare out at us menacingly, while our macabre host himself has one eye shut while the other is open wide. He too fixes us with his gaze in preparation to embarking on the telling of the stories that follow.

And so we begin the first of these tales, FRIGHT! scripted by Robert Kannigher and illustrated by the incomparable Alex Toth. Regular readers of my blog entries will know how excited I am by the work of this particular artist despite having only recently become familiar with his work. This is a great introductory page to the story. The protagonist, Gerald Rogers, is surrounded on all sides by a sinister array of ghouls, demons, zombies and scar-faced hooded figures. The eyes of the surrounding uglies focus on the panicking Rogers, whose own eyes look desperately off to the side, reinforcing his vulnerability and hopelessness.

On the following page, we see Rogers' face almost completely obscured by shadow, as he faces away from the men trying to pressure him into doing something he doesn't want to do-- stay in a haunted house. But his eyes seem to be shifting about uncertainly, this time going in the opposite direction to the previous page, suggesting his indecision and desire to find an escape route from these men.

Then we see two of the hooded nasties again staring directly at him, their eyes the seeming source of their power. To escape their clutches it seems like Rogers must avoid their eyes, and again he looks pitiably away from them, this time the strain producing a tear which rolls down the cheek of his upturned face. In the next panel the hooded figures continue to stare impassively, this time out at us the reader. Their leader's eyes are drawn with thick lines encircling them, increasing the sense of menace and ensuring we know this fellow is different and in charge. In this panel Rogers, having agreed to their demands, looks relatively calmer, but still can only look towards them with a sideways glance.

As the story flashes back to explain the events leading up to Rogers' predicament we meet the object of his affection, Fraulein Helga. A vacuous porcelein beauty, Helga asserts that she is only interested in men whose faces bear the scars of duelling. Put simply she is after a man with experience. The innocent, unscarred Rogers, attempts to make eye contact with her but she simply looks past him, her heavily lashed pale blue eyes dreamily focusing instead surely on some undefined fantasy brute ready to wave his sabre for her.

Indeed, the barely concealed parallel in this story between fencing and sexual adventure is entirely the kind of adult subtext I have come to expect in these anthology stories. But if Rogers is the sexual novice, yearning for his first experience, he is contrasted with the story's other main character, the fencing master Rausch, who logically must be the character who is the most sexually active. Toth sets him apart from the other characters explicitly through the way he draws the drained man's eyes.

Rausch's sinister, diabolical appearance places him alongside scores of creepy, malevolent figures in the readers' consciousness such as might be played in a movie by Vincent Price or Christopher Lee. Perpetually drawn with these thick rings around his eyes, Rausch is the man of considerable 'experience', the one who has 'fenced' so much he has become the master of it. But that mastery has come at a price. The heavy rings reveal the toll such an effort has taken--

In fact one panel is an extreme close-up revealing the heavy grey rings encircling his eyes, overcast by his thick bushy brows. Despite the fact that this is a close-up, Toth does not allow his colourist any chance to diminish the darkness of this man's soul, instead rendering the pupils and irises as if they are deep dark holes.

And so in order to be allowed to enter the fencing fraternity, and have even the remotest chance of impressing Helga, Rogers is required to prove his courage by spending a night alone in a haunted house, cheekily referred to as the House of Mystery.

Fittingly at the moment that he determines which of the houses the fraternity is referring to, his eyes are hidden in shadow. This is his moment of blindness, as (spoiler alert!) he chooses the wrong house.

Almost immediately he is confronted by the manifestation of a crimson clad figure. Identifying this to be "the devil himself", Rogers' reaction is to stare boldly at the figure and laugh incredulously. Toth, for the first time, draws Rogers' eyes fully open and the colourist opts to make them the same shade as the beauteous Helga's. The pupils are mere dots. At this moment Rogers describes the appearance of this pantomime demon as "a grand trick"-- his eyes are wide open to the machinations of the fencing fraternity-- he has seen through their lame attempts to spook him with "theatrical effects".

But something in the above portrait of Rogers suggest another dimension-- for despite his confidence there is a vulnerability about this image, and again it's all in his eyes. Indeed he will not be the first -or the last- foolish innocent to walk wide-eyed towards his doom.

When Rausch confronts Rogers with the revelation that he has spent the night in the wrong house Toth goes to town with the thickest shadows yet framing his eyes so that they become practically a mask.

And at the story's conclusion, Toth chooses to depict the traumatised Rogers in almost the same way as a few pages earlier with a close-up on his wide-eyed face. But this time his smile is replaced by a grimace. The eyes remain wide open and are again shaded a smudgy blue. But this time the dots which represented the pupils are absent, giving them now the quality of deadness and despair.

Then as he is seen finally locked away his face is drained and the eyes ringed with lines more like those of Rausch. But his eyes have not aged with the wisdom and experience of sexual delight, but with a more terrifying knowledge gained through his encounter with the supernatural.

Moving on this issue's second story, A WITCH MUST DIE!, it also interesting to see how the characters' eyes play such a significant role in the story-telling. Written by Jack Miller and drawn by Ric Estrada and Frank Giacoia, the story takes place in Salem, Massachusets and so naturally focuses on accusations of witchcraft. The story starts with Esau, another young, wide-eyed romantic (albeit a married one) voyeuristically spying on another man's wife.

The object of Esau's gaze -and affections- is Ruth, a woman who is about to be accused of witchcraft. A dark-haired beauty with a 10-year old daughter, Ruth is depicted in the title panel staring directly out at the reader, inviting us to trust and to fall for her too.

Her accuser is Esau's jealous wife, Jennifer, who is convinced he has been "bewitched and dazzled" by Ruth. As she observes another woman being dragged away to the stake and realises how to get rid of her rival, the artists capture Jennifer's devious thoughts by casting heavy shadows over her eyes.

The effect is repeated later as she leads the incensed community towards the woman she has convinced them is a witch.

And what of that incensed community? Well, here they are, at the moment Jennifer tricks them into believing a witch is flying over their village on a broomstick. They are all wide-eyed in terror and open-mouthed gullibility.

And here they are again, all pitchforks and flaming torches, gathering at Ruth's house and demanding her husband Jacob hands her over to them. Look into their eyes and you see the brainwashed eyes of any angry mob, goaded to violent action through prejudice and ignorance.

The wise Jacob is unconvinced by their preposterous assertions that Ruth is a witch. He knows how paranoia leads to wild accusations and leaps to his wife's defence. His eyes look world-weary but sensible in contrast to their wide-eyed lunacy.

And talking of moon-eyed idiots, here's young Esau again, unashamedly gazing straight at Ruth in front of both her husband and his own wife. This is a great panel in terms of the four different characters' emotions being made explicit primarily through the position of their hands and especially their eyes. It's probably my favourite panel in the whole story.

I also love the way the artists choose in the panel below to draw Jacob's eyes looking off to the side somewhat shiftily as later he reveals a hidden rope to help rescue his imprisoned wife. Until this point he has been presented as an honest, upright fellow. Here, realising his wife is victim of what he considers to be "an insane law" imposed by "superstitious fools", it is the shifty sideways glance which best symbolises his personal shift to becoming a law-breaker.

Jacob escapes with his wife and child and finds himself in woods his daughter describes as being "too dense to let the sunshine in -- ever!" Choosing to settle here they are confronted by Ashtari, who introduces himself as "Leader of ancient tribe who dwell here in hallowed ground of ancestors". His eyes glare down at them menacingly. It's a chilling moment.

We close in on the mysterious Ashtari, whose dark-shadowed eyes now stare out at us imposingly. It is the second time in this story that a character has done this, breaking the fourth wall almost, but at the same time creating a sense of unease in the reader, suggestive of the characters' hidden powers.

As Ashtari casts a spell on a nearby tree, little Hester also seems to be looking directly at us. But this is not a look of powerful imposition, instead it is a wide-eyed look of panic as the girl sees the effect of Ashtari's magic--

The story concludes with Ruth (spoiler alert!) revealing that she is a witch after all, and having cast her own spell on the falling tree she crushes Ashtari and turns towards her startled husband. Suitably in an issue in which so much of the story-telling has centred on the way the characters' eyes are drawn, her eyes here are depicted surrounded by a green glow. It's all that's needed in fact in an ending that conforms effectively to the "show, don't tell" adage of good story-telling practice.

I probably recall these stories as being better than they were, simply because at the age of 13, I wasn't sophisticated enough to see the twist endings "coming from incredibly early on", to use your phrase. At least, that's the story I'm going with. :-) Of course, as your review makes clear, the art -- most especially Toth's -- holds up.

ReplyDeleteAlso must say that I thought your detailed analysis of Adams' cover was fascinating -- it's the kind of thing I wish I was better at, frankly!

Thankyou for your kind words, Alan! Glad you liked the cover analysis especially. I think if I looked again at some of the stuff I was reading at 13 (1980!) I'd see it very differently to how I remember it. I think that's why doing this blog works for me because I have little or usually no prior knowledge of what I'm reading but a lot of people reading my commentaries are already fans from way back. It's kind of back to front to what is more often the case, and occasionally winds up people with very fixed ideas about these things!

ReplyDelete